Who was ‘the Last Knight of the King’s Gambit?’

Such a romantic description, yet the name of the player, who was at the height of his powers during one of the Golden Ages of Chess, eludes most people when they eulogize the games of Jose Raul Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine and a whole range of other titans from the 1920s and 1930s.

Yet this player was, in a way, a Candidate for the World Chess Championship, as he played in the famous New York tournament of 1927, which was won (very comfortably) by an imperious Capablanca, who went on to lose his title – the surprise of many – the Alexander Alekhine later in the year.

Alekhine finished second in New York and readers will find the names of Aron Nimzowitsch and Frank James Marshall spring immediately to mind when trying to recall the four other competitors.

The two most likely to be forgotten are Milan Vidmar and…Rudolf Spielmann.

The latter is the player whose name we asked about at the start of this post.

In reality, of course, nobody other than Capablanca and Alekhine were really likely to take either of the first two places in New York, especially given the quadruple round-robin format, which made surprise results rather difficult.

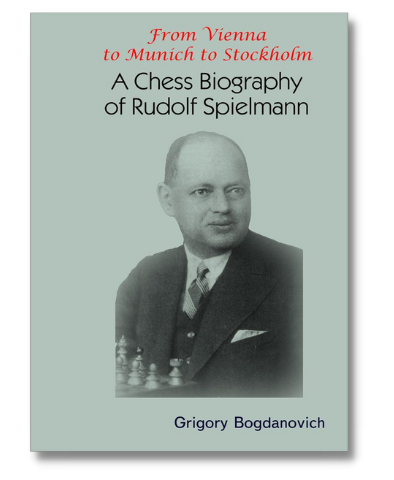

Nevertheless, even though Spielmann’s play was too frustratingly inconsistent to enable him to make a substantial impact at the very top level, his creativity and originality brought him many stylish wins against some of the best players in the world and they can be found in the excellent new book, A Chess Biography of Rudolf Spielmann (Elk and Ruby) by Grigory Bogdanovich.

The author has clearly worked hard to assemble a large amount of very interesting material and games, just as he did with his earlier books on Bogoljubov.

Spielmann’s life story was certainly not without its tragic elements, as readers will discover as they delve into the book.

However, to keep this blog post on the positive side of life, we shall return to the old, romantic, and possibly suspect King’s Gambit.

Spielmann’s own article, ‘From the Sickbed of the King’s Gambit’ is an historical lament in recognition that 1. e4 e5 2. f4 was, perhaps, nearing the end of its life at the higher levels of chess. However, as it was written 100 years ago, hindsight shows us the death knell was sounded prematurely (see, for example, the magnificent King’s Gambit games played by Boris Spassky, who numbered various other chess kings amongst his victims, including Bobby Fischer, Anatoly Karpov, and David Bronstein).

Here is a snippet showing Spielmann in his finest King’s Gambit form.

Spielmann – Grunfeld

Teplice Sanov, 1922

Grunfeld tried to repel the invaders with 19…f5 but was rocked back by 20. Rxf5! (and 1-0, 31).

Despite the lasting memory of Spielmann’s strong association with the King’s Gambit, the book makes it clear that he was far from a ‘one trick pony.’ Indeed, his positional play was of a very high standard too (it would not have been possible to become one of the world’s top five player by f-file sacrifices alone) and one thing I didn’t realize until I read this book was just how many matches Spielmann played. It was over 55 and his opponents were of a generally very high standard, including Reti, Tartakower and Bogoljubov.

I can easily recommend this new book to anyone interested in chess history and sparkling games, which left no opponent feeling safe.

In Spielmann’s own words: ‘I’m coming after you!’

Sean Marsh

- Book Review: Moves 3 to 10 by Nery Strasman - August 9, 2024

- The Life and Games of Dragoljub Velimirovic (Volume 2) by Georg Mohr and Ana Velimirovic-Zorica - July 23, 2024

- Review: Chess Informant - June 7, 2024