Imagine winding up your office work earlier to get back home for a crunchy cup of popcorn, the warmth of a comfortable couch, your family around you and your favorite soccer team in action fighting for, say, the World Cup. When everything seems to be a picture-perfect moment, all of a sudden your team loses, thanks to this one guy who attacks a player in the opposing team with a headbutt and gets a red card, leaving the team in big trouble.

That agony of our favorite team losing their game and the invective we throw at the person responsible for the loss! We’re all had our moments, be it the NFL or FIFA World cups or the IPL cricket.

But guess what? it happens all the time in our 64-square world. Do we notice it?

Introducing the black sheep:

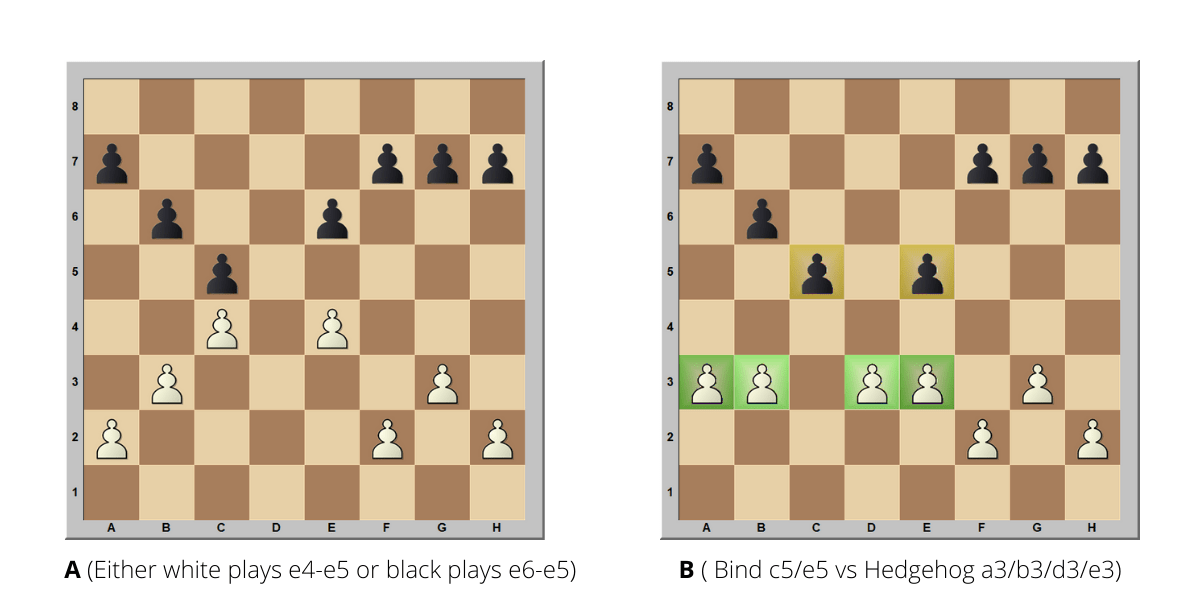

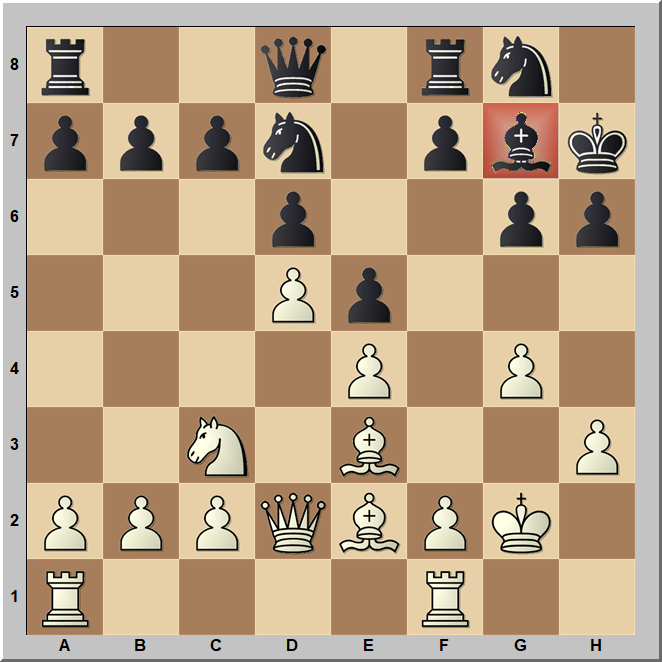

I played white in the below position again a talented young player. The position is right out of the opening (Typical symmetrical English style middlegame) and it’s time for black to make a few strategic decisions.

One important decision is where to develop the black queen and the e7-bishop. The general plan for black is based on the pawn formations. Queen goes to a8, and the black bishop goes to the more secure f6 or g7 square.

But my opponent played Bd6 with the plan of going to b8. This turned out to be a strategic error. By playing e4 and forcing e5, we reached a pawn structure where the Bishop on d6 is going to be a burden for black.

Like the proverbial piece of straw that broke the camel’s back, One strategic mistake followed another. After Rfd1 ( Clearing f1 square for future activities), black played Qe7 instead of Qc7. The problem with this move is that it blocks the future Bishop maneuver Bd6 to f8 to g7, and also creates future trouble for the kingside if the bishop doesn’t occupy g7 quick enough. Black also missed another window of opportunity by missing out Ne6 (instead he played Bc7)

Black’s dark-square bishop turned out to be the black sheep that helped white win the game in an elegant style.

Here’s an example where a player is cautious about his possible black sheep and maneuvers it out of trouble. The game is from the book Maneuvering: The Art of Piece Play by Mark Dvoretsky and published by Russell Enterprises.

The game was between two Grandmasters Stefano Tatai and Larry Christiansen, played in the year 1977 at Torremolinos, Spain.

The presence of such black sheep (or bad pieces) can actually be a good thing, especially if they are on the opponent’s team. I love the chapter Obstructive Sacrifices from the fantastic classics The Art of Sacrifices in Chess by Rudolf Spielmann.

One of my favorite games from the chapter is his game against Salo Landau back in 1933! Try guessing Spielmann’s move when you browse the game, especially where he sacrifices a pawn to obstruct enemy piece coordination and the beautiful final finishing touch.

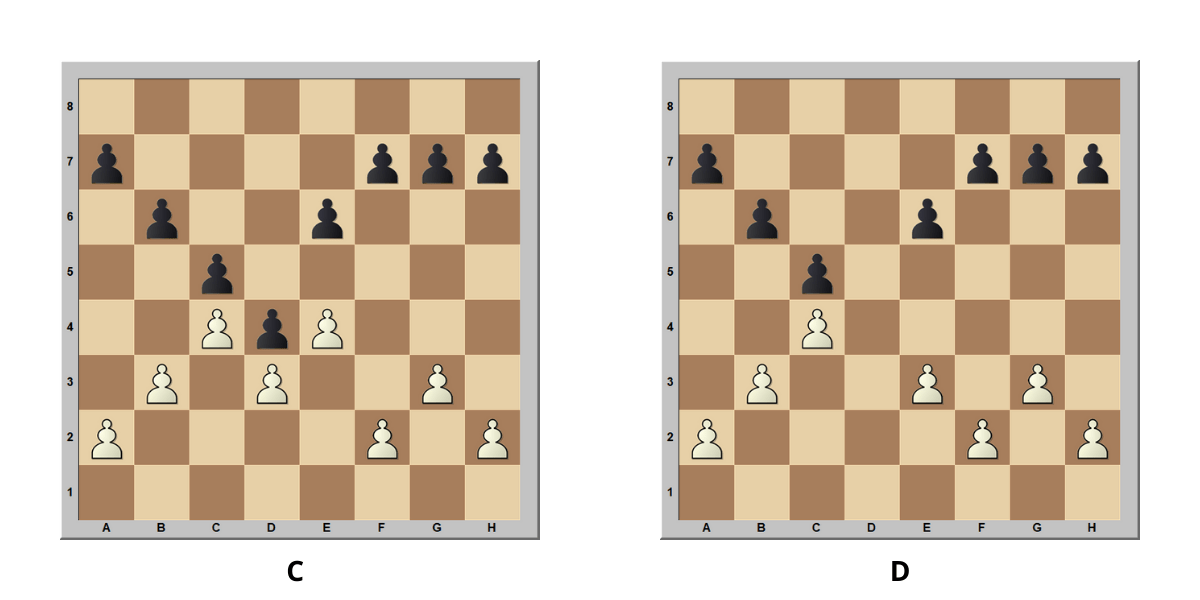

A similar idea can be found in the advance carokan g4 variation. Here’s a good example to illustrate the idea.

Here are a few exercises to consolidate our learning. Think about which piece is likely to become a bad piece or black sheep in the future, the best square for the piece and how you can maneuver it to the square. The exercises are from the chapter “Pieces” from the book Grandmaster Preparation: Positional Play by Jacob Aagard.

Position 1:

Position 3:

Thank you for reading. I’ll be happy to hear your thoughts.

Signing off for now,

Arun from Forward Chess Team.

- Review: Perpetual Chess Improvement - May 9, 2024

- Dark Mode is now live on Web Reader - April 30, 2024

- Book Review: Tal Botvinnik 1960 - April 24, 2024