Whilst we all remain on the edge of our seats watching the current World Chess Championship between Ian Nepomniachtchi and Ding Liren, let’s take a look back at former Chess World Champions. In this Part 1, we will travel back to the first official World Chess Championship in 1886 up until 1946, taking a look at the first 5 champions:

The Beginning: Wilhelm Steinitz

1886 to 1894

By the time Steinitz entered the chess scene, professional play and international tournaments were already popular, dominated by chess giants such as Adolf Anderssen and Paul Morphy. The chess style at this time can be characterized as aggressive and attacking, where plans were formulated along the lines of a kingside attack (this is very prevalent in Morphy’s games). Steinitz committed his life fully to chess, unlike Morphy who stopped playing at the mere age of 21 to pursue law. This meant that these two greats never got to face off at the chess board.

Steinitz’s approach was somewhat more technical, scientific, and strategic, which, paired with a strong work ethic, paved the way for a new style of chess. He believed that play should be directed to the Queenside and Center rather than just Morphy-style Kingside assaults, and developed the theory that players should collect small strategic advantages to prepare a winning attack. Furthermore, and what players are still influenced by today, was Steinitz’s belief that the King is a powerful piece and should be used for attack and defense.

A lesser-known fact is that Steinitz actually took a break from international tournament play for 6 years in 1876! During this time, still devoted to the game, he was a chess writer and analyst, providing in-depth analysis for world-class chess columns. He returned to international top-level play in 1882, a time when J Zuketort had been dominating tournaments. With the assistance of financial backers and an eagerness to settle who holds the seat to the throne, the first formal World Chess Championship match was held in the US in 1886 between these two chess giants.

With his superior understanding of openings, creativity, and strategic play, Steinitz won the match (decided by the first player to get 10 wins) and became the first official World Chess Champion. He went on to defend his title three more times against the Russian Mikhail Chigorin (1889 & 1892) and Hungarian Isidor Gunsberg (1890-1891) until he was dethroned in 1894 by the German Emanuel Lasker.

Here is an exemplary game between Steinitz and his challenger, Chigorin during their 1982 World Championship match as shown in Modern Chess: From Steinitz to the 21st Century:

Emanuel Lasker

1894–1921

Only 25 years old when he first won the title against the much older Steinitz in 1894, Lasker acknowledged and respected Steinitz’s scientific approach and rules to chess, and went on to build on them by theorizing new principles in a much less stringent way. Steinitz believed that players should strive to find the best move in any position, whereas Lasker understood that humans are not always capable of such perfection and that mistakes are inevitable. He saw chess as a battle between two minds, both of which are capable of making mistakes. The better player, according to him, is the one who understands and can comfortably play the position which can be attributed to understanding basic chess principles guided by logic and common sense.

Still today, Lasker is widely considered as one of the best players of all time mostly due to his record of having the longest reign of any World Champion in history – 27 years!

Let’s take a look at a game between Lasker and Steinitz at their 1894 World Championship match:

Lasker was also one of the best tacticians and calculators in chess. Step inside his shoes: here is a tactic taken from a game played in 1890 against Jacques Mieses:

Black to play. Can he play 12…Rd8 or does he have to defend the h7-pawn?

José Raúl Capablanca

1921–1927

The Cuban World Champion Capablanca is known for many aspects of his chess style, but arguably most of all for his positional understanding and endgame play. He did not necessarily adhere to any previously established rules, but rather followed his own and would find the correct way to play in most positions, adopting the nickname the “Human Chess Machine”. Capablanca was considered to be an intuitive genius – he understood chess so naturally and in ways that cannot be defined. This machine-like depiction can also be attributed to his incredible speed of accurately assessing positions and subsequently playing the most accurate moves.

His gift for chess was already prevalent at the mere age of 16, and interestingly enough, it was his predecessor Emanuel Lasker who had talent-spotted the young prodigy at the Manhatten Chess Club in 1905. Soon enough the young Cuban was ready to take the throne himself.

Unfortunately, the war years 1914-1918 halted the World Championship cycle, but Capablanca continued to live up to his greatness by playing and winning multiple strong tournaments. After being previously denied to challenge Lasker, eventually in 1921 a match was set up between the two players and Capablanca triumphed as Champion when Lasker resigned from the match after 14 games (which was supposed to be 24 games).

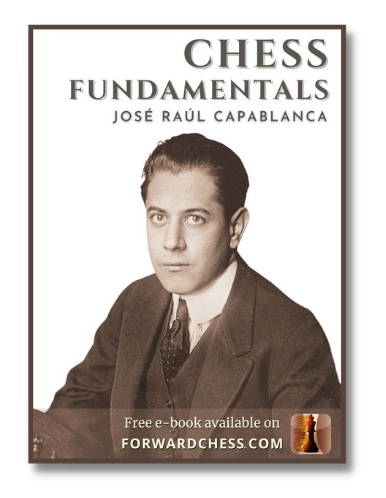

Capablanca was also a notable author, writing one of the best chess books, Chess Fundamentals – a timeless work that covers strategic fundamental principles that every chess player should know. Have a look at the free e-book version here on Forward Chess!

Have a look at his game victorious game 11 against Lasker in their 1921 World Championship match: (annotated by Capablanca himself)

Play like Capablanca! In his book “Capablanca: A Primer of Checkmate“, author Frisco Del Rosario shines light on checkmates inspired, played, and created by Capablanca. Take a look at this mate coined after him, Capablanca Mate where “the Rook gives check and covers the seventh rank, while the Knight covers the potential flight squares on the eighth. After that, it is a matter of guarding the checking piece from capture”

Can you find this 4-move mate tactic played by Capablanca in a game against A. Souza Campos in 1927?

Alexander Alekhine

1927–1935 and 1937–1946

Alekhine’s life is an interesting one to reflect on. Born into a wealthy Russian family, he was fortunate to have many opportunities to play chess competitively on an international level and very soon placed himself on the podium with other great players. However, his life was not only one of comfort as he would go on to spend a brief period of time in a German prison, and even ended up in a hospital as a result of serving in the Russian ranks. Eventually, he won the first Soviet Chess Championship in 1921.

Imaginative and attacking play would be the best way to describe Alekhine’s chess style. This, along with his determination to be the best, saw him successfully battle for the title against Capablanca in 1927. His style of playing directly opposed the intuitive Capablanca’s as his success was attributed to hard work, study, and theoretical research. He wrote many chess books and contributed immensely to opening theory, still played today.

Alekhine successfully defended his title twice against Efim Bogoljubow, but in a shock to the chess world, lost against the weaker Max Euwe in 1935. However, not long after in 1937, a rematch saw Alekhine regain the title. Impressively, Alekhine was the only World Champion to die a champion. Of course, his final years were full of controversy and speculation, but the fact still remains that he holds this feat!

In his book, Alekhine: Move by Move, author Steve Giddens showcases Alekhine’s competitive nature and tactical ability by studying Alekhine’s games, enabling the reader to learn from the masterpieces. Here is an example of a simul game shown in the book:

Max Euwe

1935-1937

Max Euwe is by no means the greatest chess player of all time, but he was talented and so much so that he was able to briefly dethrone Alexander Alekhine as World Champion, even though he was considered to be an amateur. His success can largely be attributed to his research skills (unsurprising as he was a math teacher with a doctorate), which he used to prepare opening blows to the unprepared Alekhine.

Furthermore, Euwe cemented his role in chess as the FIDE president from 1970-1978, as well as an author with multiple books, most notably “Judgement and Planning in Chess”.

Take a look at game 26 (out of 30!) illustrated in the book Modern Chess: From Steinitz to the 21st Century:

Featured Books

Have any thoughts or questions? Let us know in the comments below!

- The Power of Pattern Recognition: The Woodpecker Method 2 - August 20, 2024

- Rock Solid Chess: Volume 2 - February 21, 2024

- Unsung Heroes of Chess - February 19, 2024