Review: The 100 Endgames You Must Know Workbook

“It is a well-known phenomenon that the very same amateur who was able to conduct the middlegame very creditably appears to be quite helpless in the endgame.” – Aron Nimzowitsch in “My System” (Quality Chess edition, 2007).

Aron Nimzowitsch may have overestimated the middlegame skills of most amateur players, but he was surely correct in the endgame. Endgame theory is challenging to master, and there seems to be a never-ending amount of theoretical knowledge to learn. Moreover, in Nimzowitsch’s day, adjournments were possible, typically after 40 moves, and an endgame had usually been reached by this stage. Players could then study the resulting endgame at home, which helped enormously to overcome any gaps in endgame knowledge. Nowadays, competition games are completed in one session, and endgames are usually played under tight time constraints. As GM John Nunn noted in his book “Grandmaster Chess Move by Move” (Gambit Publications, 2004): “This effectively makes a well-played endgame an impossibility and a quick look through the games played in events using the FIDE time-limits shows the destruction wrought on endgame play.”

While nothing can be done about the current time-limits, GM Jesus de la Villa tried to ease the learning problem in his book “100 Endgames You Must Know”. As the title suggests, de la Villa compiled what he considered the 100 essential endings to study. Of course, it’s possible to argue with his choices, but since the book is now in its 4th edition, it’s safe to say that his choices have been well-received. The current book is a sequel to the previous book, and it contains 300 exercises for the reader to solve. Most exercises are cross-referenced to the appropriate endgames in the previous book, so that readers can refer to that book for further theoretical details. However, while it certainly helps to have the previous book, it is not essential, and the current book can be used as a stand-alone book.

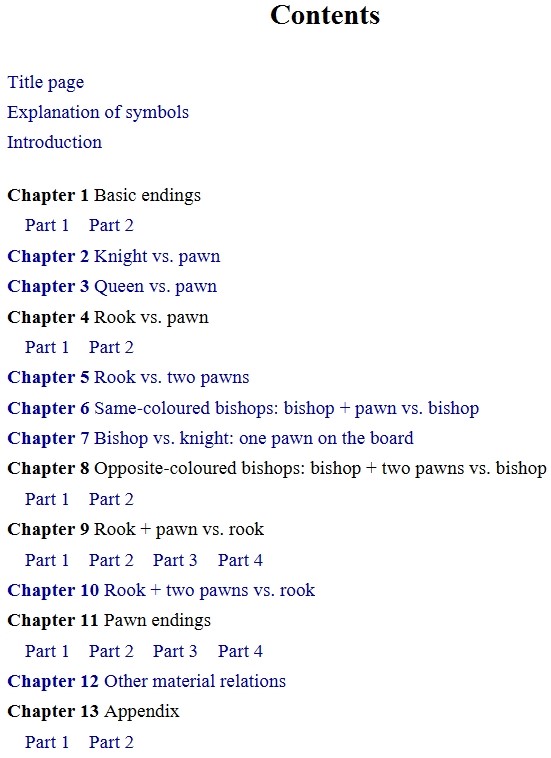

The table of contents above shows the endgames covered, and these correlate to those in the previous book.

Apart from Chapters 11 and 13, each chapter starts with some basic positions that are critical to understanding the theory behind the exercises in the appropriate chapter, and the solutions of the exercises frequently refer to these positions. The exercises in each chapter are ordered in increasing level of difficulty, although the author states that this ordering is somewhat subjective. He also suggests which exercises are appropriate to solve based on your rating. The tasks required of the reader are varied. Some simply ask if it’s possible to win or draw the position, while others ask the reader to choose the best move from the options given in the exercise. Many of the exercises illustrate blunders and missed opportunities, even by elite players, and these blunders reinforce Nunn’s comment above. The solutions are detailed and provide clear explanations, and they include text, analysis and endgame tablebase references where appropriate. Some solutions also include visual markups on the chessboard to make general statements about critical positions. One such example is shown below.

With White to move, this diagram shows the squares the white knight must occupy for it to be able to deliver checkmate.

Two instructive examples from the book are given below, with annotations from the book. In the first example, a young Magnus Carlsen goes wrong. The question is “Only one move draws the game for Black. Which one?”

In the second example, the question is “Can White hold his own?”.

In summary, there is a lot of instructive material in this book. You may not like endgames any more after carefully studying the book, but your endgame skills will be greatly improved.

- New Release: Chess Analysis – Reloaded - March 9, 2024

- Review: The Art of The Endgame – Revised Edition - February 14, 2024

- Review: Study Chess with Matthew Sadler - December 13, 2023